Google File System

Actual Paper

Trivia

- The original paper was published in 2003 at SOSP (Symposium on Operating Systems Principles)

- Distributed file system built for Google’s computational needs - to support hundreds of clients concurrently reading/writing to large files, while ensuring HA, performance and reliability.

Original Motivation

- Google stored dozens of copies of the entire web.

- Google was serving thousands of queries/second. Each query reads 100s of MB data and each query consumes many CPU cycles.

- Needed a large, distributed, highly fault tolerant file system.

- To build a replicated storage layer using commodity hardware – to power batch jobs. (Eventually powered other projects)

- Since GFS was primarily designed for batch workloads, it is optimized for appends rather than modifying files – users are generally expected to write large files at once than modify/write small files

Assumptions / Design Motivations

- Fault-tolerance and auto-recovery needed to be built-in.

- Standard I/O assumptions (e.g. block size) to be re-examined.

- Appends are the prevalent form of writing. And most files are written once and read many times.

- Everything must run on commodity hardware with frequent component failures.

- Aggregate read/write bandwidth more relevant instead of per client.

APIs

Not POSIX compliant.

- Read (file, startOffset, endOffset)

- Write (file, startOffset, endOffset) - Not often invoked in practice

- AtomicRecordAppend (file, data)

- Data guaranteed not to be interleaved with current atomic appends

- Returns offset where data is written

- Use-case - Pubsub on GFS or Merging data

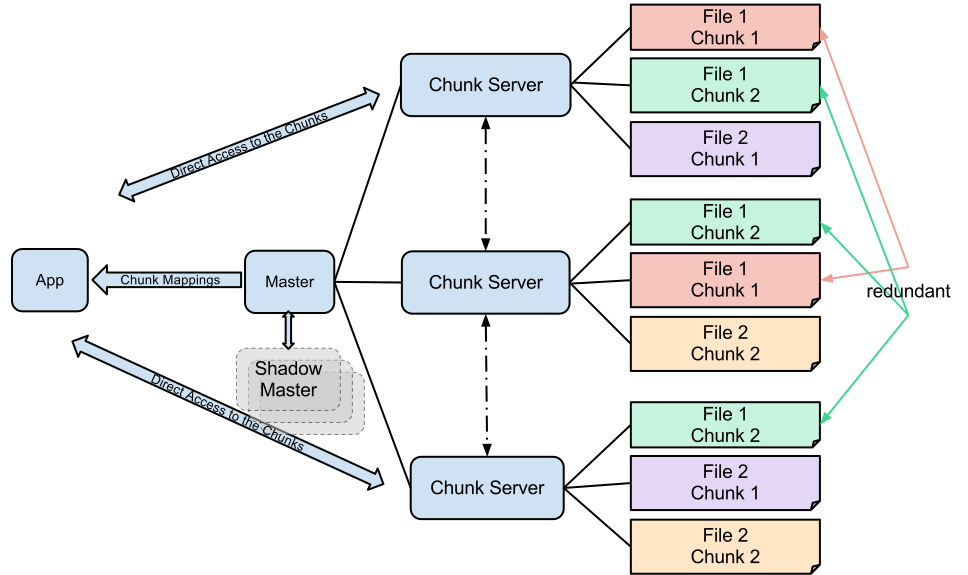

Architecture

Overview

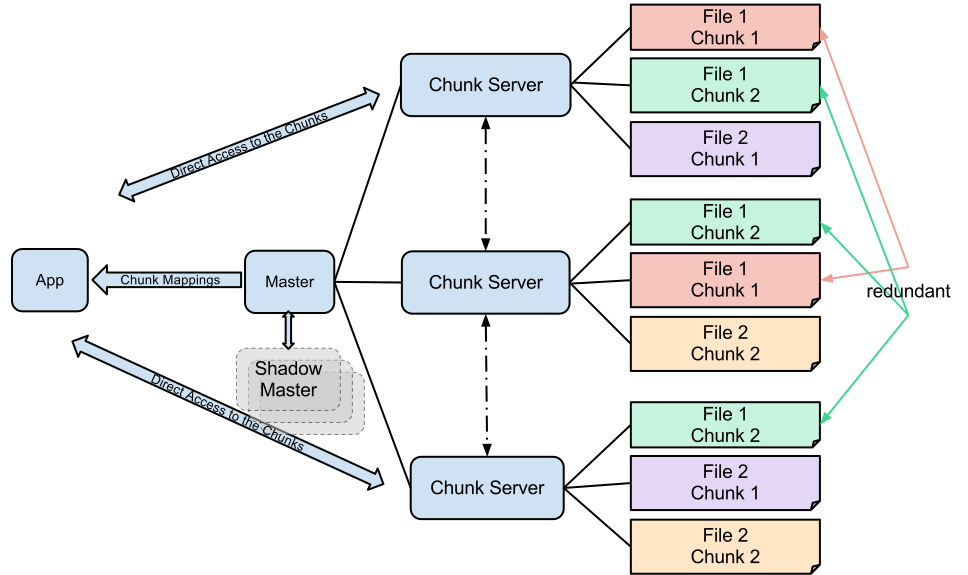

Consists of a Master and Chunk nodes.

- Master node maintains the metadata

- A lower layer (i.e. a set of chunkservers) stores the data in units called “chunks”.

- Each file is split into 64 MB chunks and distributed across servers.

- Why? For distributing load across multiple nodes for reads/writes.

- And most reads/writes happen in a contiguous block of data.

- 64MB is a trade-off between load balancing and providing a contiguous block of data size that clients usually operate on.

- Also, 64MB was a huge block size when GFS was originally designed.

- Chunks are stored as a plain Linux file on a chunkserver and is extended only as needed. (Lazy space allocation)

- Other points

- Less chunk metadata when chunk size is big - both for client side metadata caching and storage in GFS.

- Bad if there are many small files - since in the worst case, you can have only 1 chunk and many clients accessing the same file can create a hot partition. But not the usual case in practice.

- Clients are more likely to do a bunch of sequential operations. So, can keep persistent TCP connections.

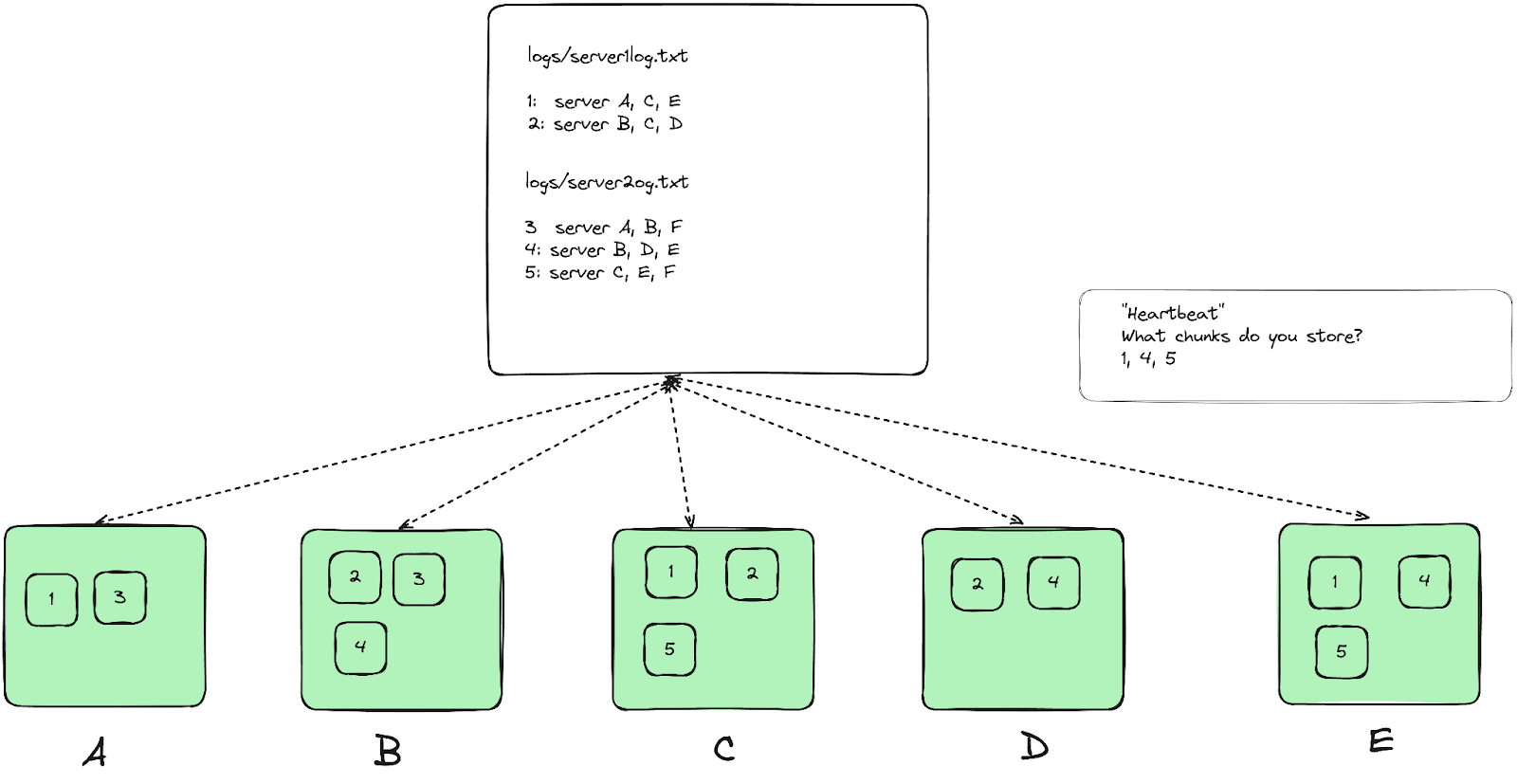

Master

Simple design. Global state allows for better decision making.

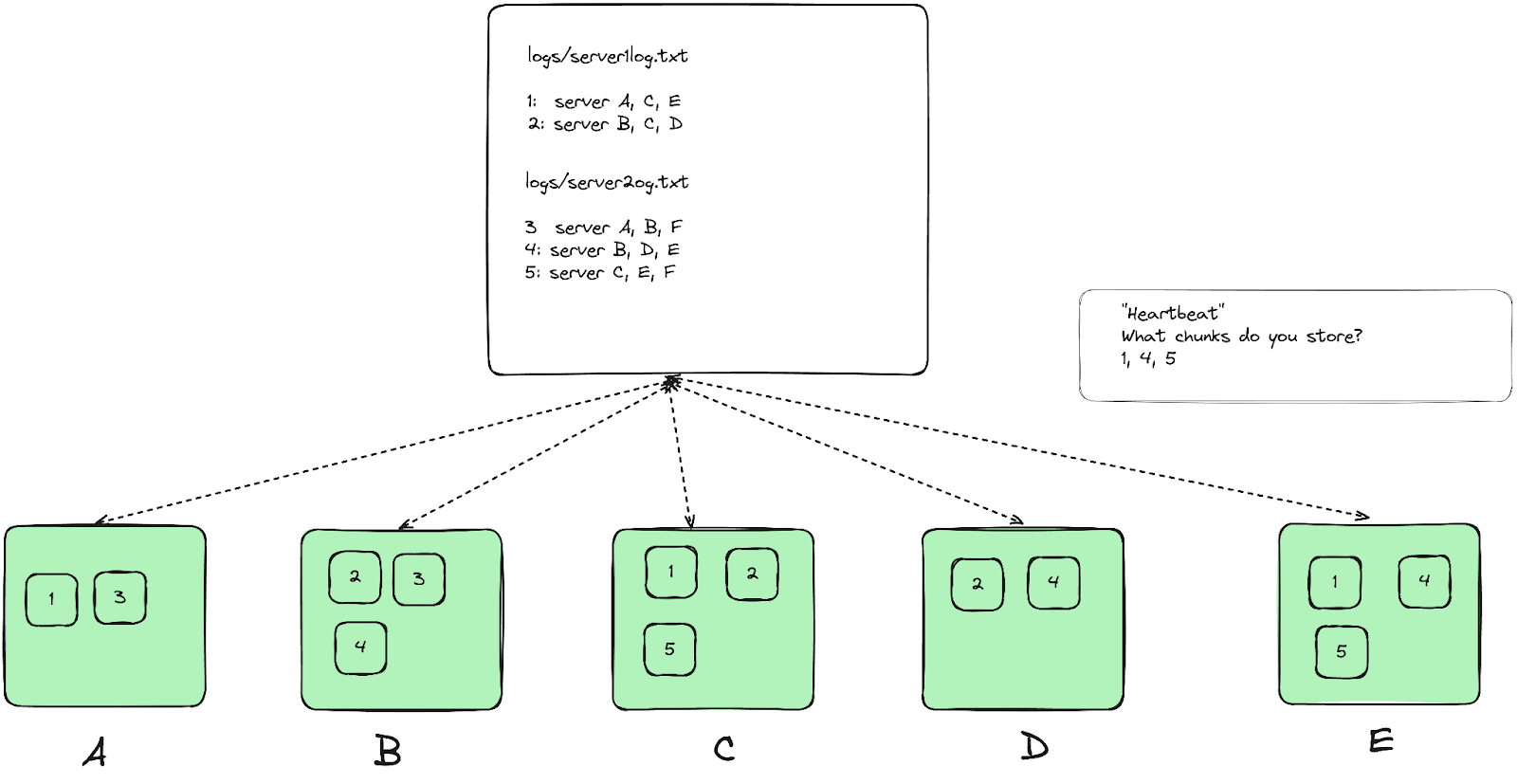

- Stores mapping between files and chunks. (filename -> array-of-chunkhandle table and a chunkhandle -> list-of-chunkservers table)

- Has prefix compression to save file names in memory

- Chunk handles - 64 bytes.

- Chunks are replicated over 3 nodes by default. (RF=3)

Chunk Servers

Operation Log

- Master stores 3 types of information

- File/Chunk namespaces.

- Mapping between files->chunks

- Location of chunk’s replicas.

- To avoid Master becoming a bottleneck, we store the above metadata in memory. But we also persist 1.a, and 1.b in disk from time to time. 1.c. not written to reduce space.

- Operation log - (glorified) WAL

- Orders all operations

- Must be written and synchronously replicated to other nodes before Master returns any data back to clients.

Handling Master Failure

- Master can replay its operation log to restore its old state

- Note - Log only contains 1.a and 1.b. Not 1.c -> location of chunk replicas.

- Solution: Master queries chunk server to identify what they hold.

- Problem: Takes a long time.

- Other problem: Op log can be very long.

- Solution: Checkpointing state from time to time. Only read logs after the most recent checkpoint.

- Problem: Checkpointing can slow down Master.

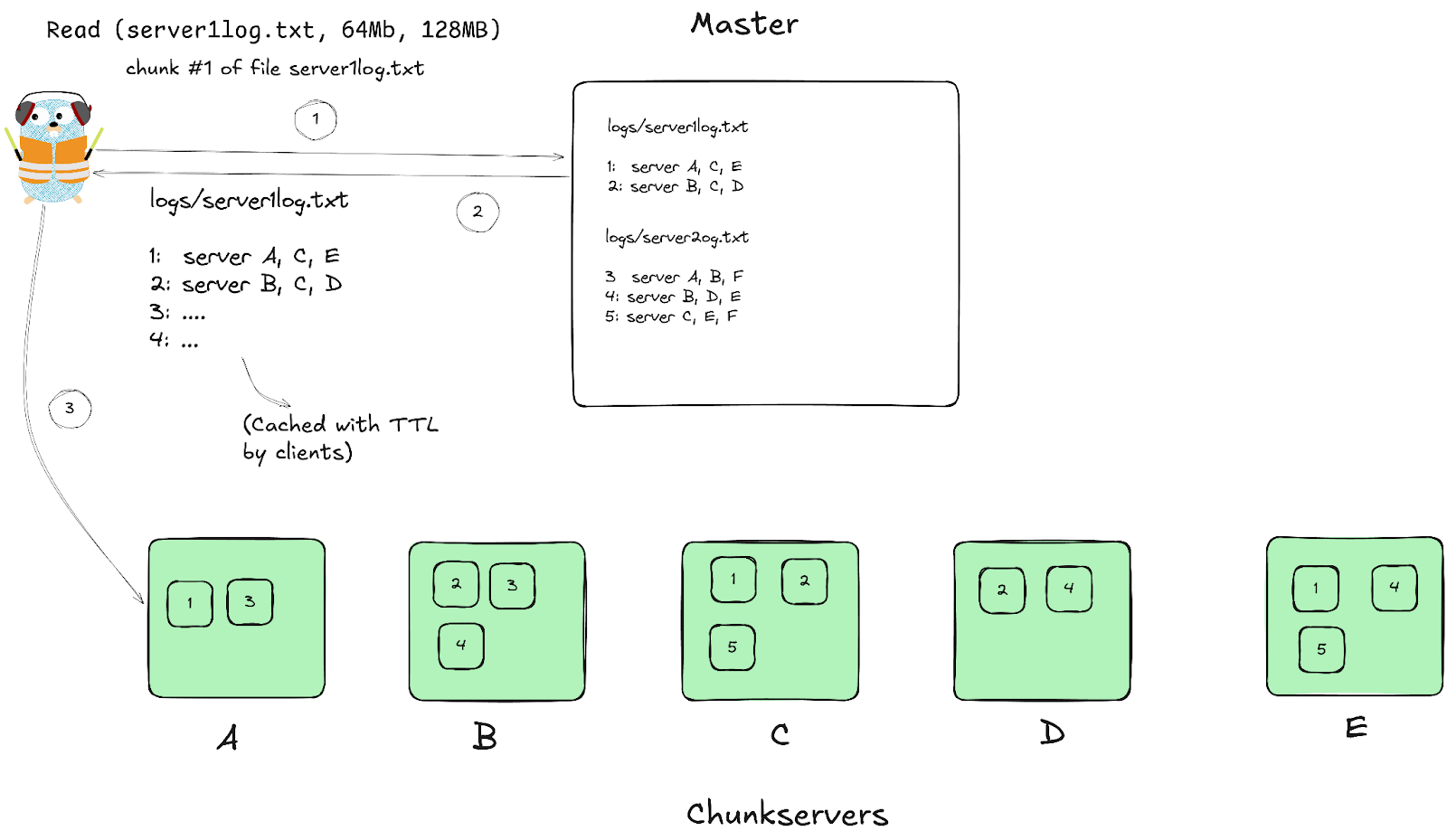

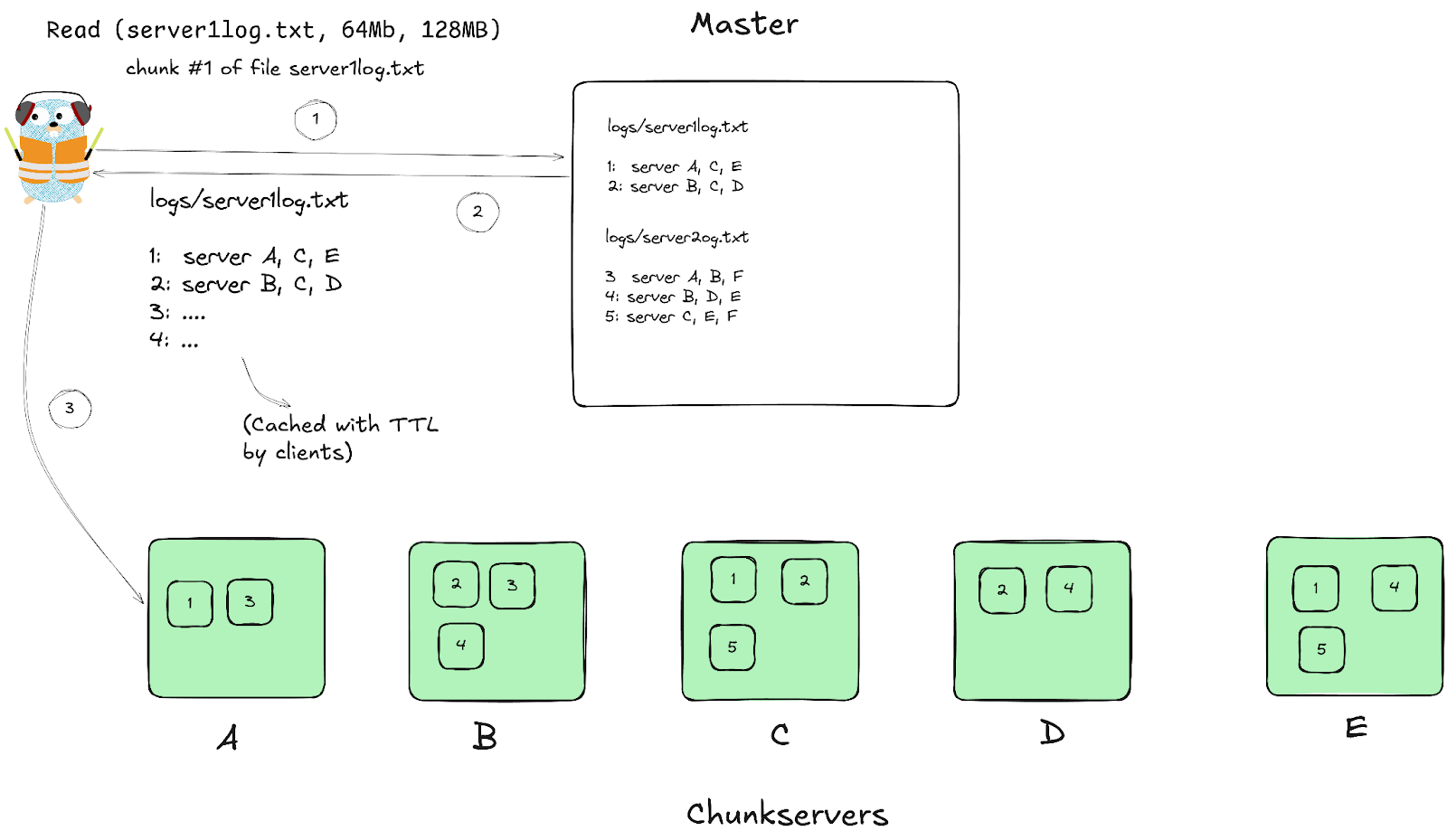

GFS Reads

- Caching and batched reads -> fewer operations for Master.

- It is possible that one of the cached replicas has missed some writes and our client may read from it.

- Since most mutations are just appends, we don’t see incorrect data. Just less than we’d like.

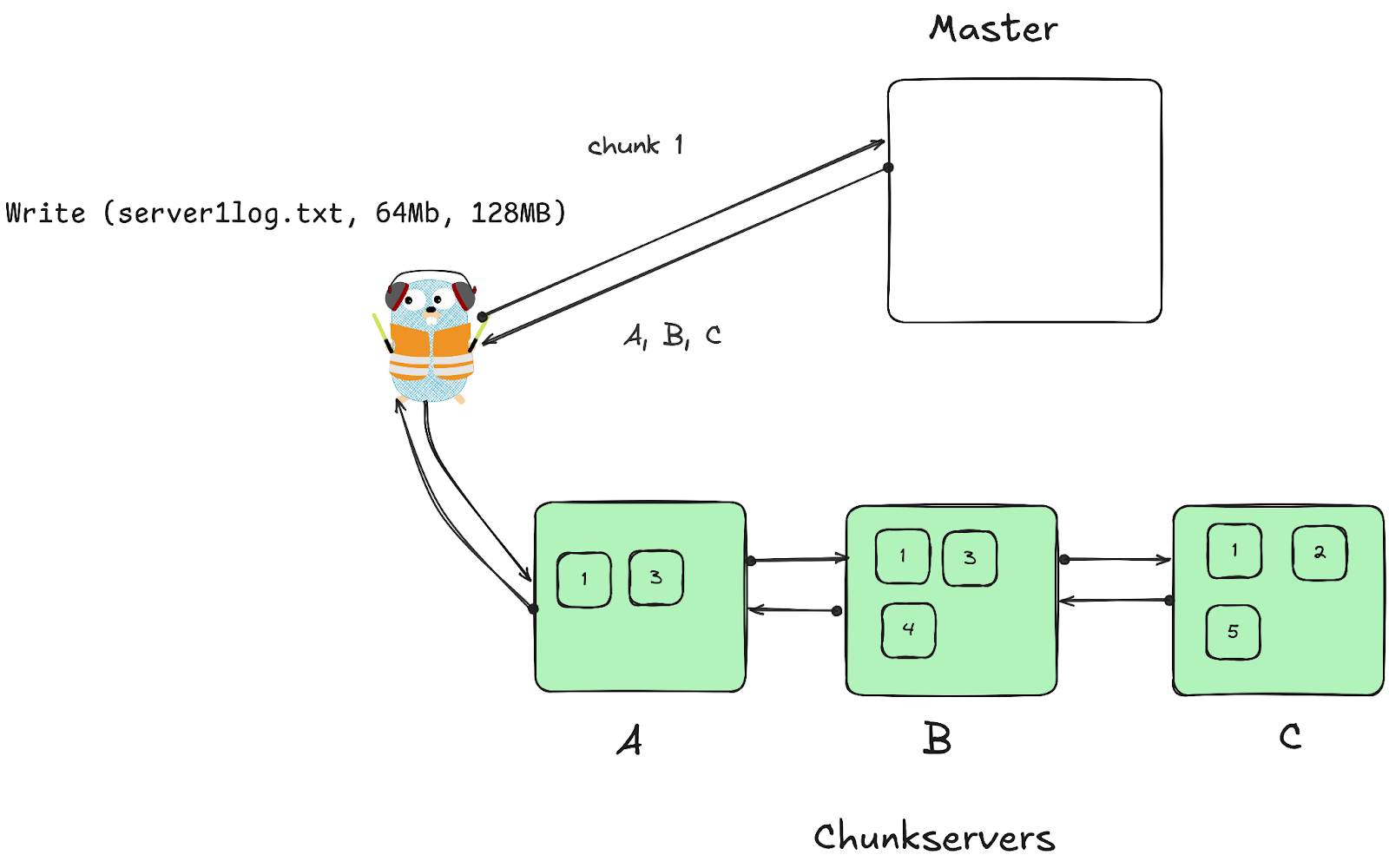

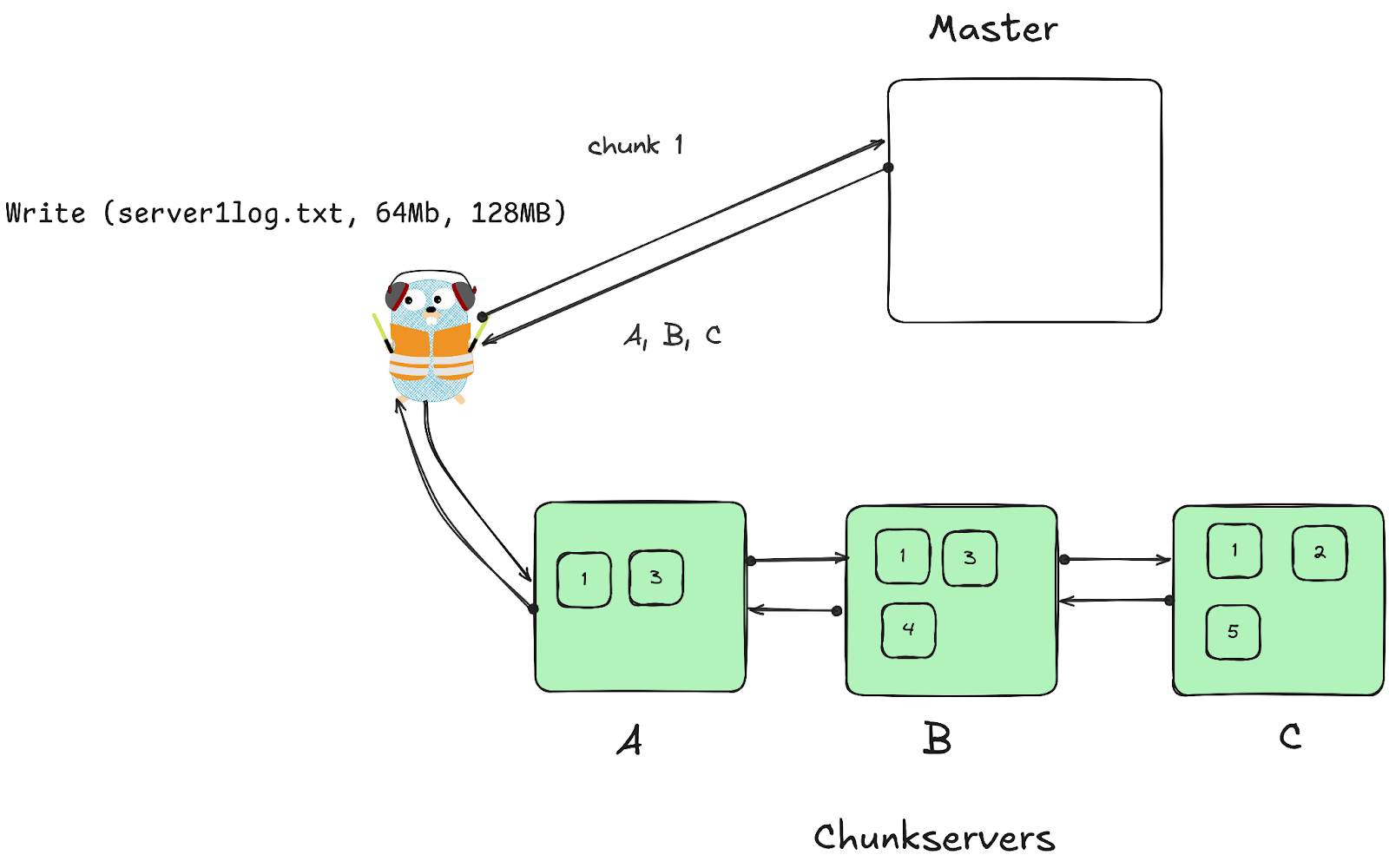

GFS Writes

Considerations

- How can we write as fast as possible considering Google’s network bandwidth?

- How can we determine an ordering of concurrent writes?

Answer: By separating data transfer and ordering of writes.

Data Transfer

- Data is pipelined. As soon as A receives packets, it forwards data to B, C etc.

- Data is always sent to the closest replica that hasn’t received it.

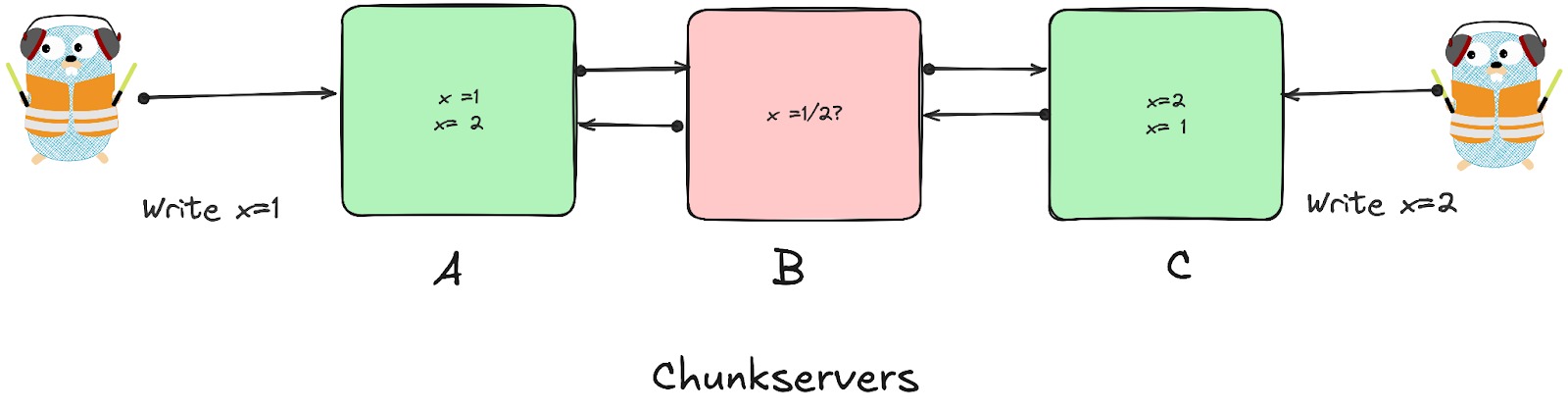

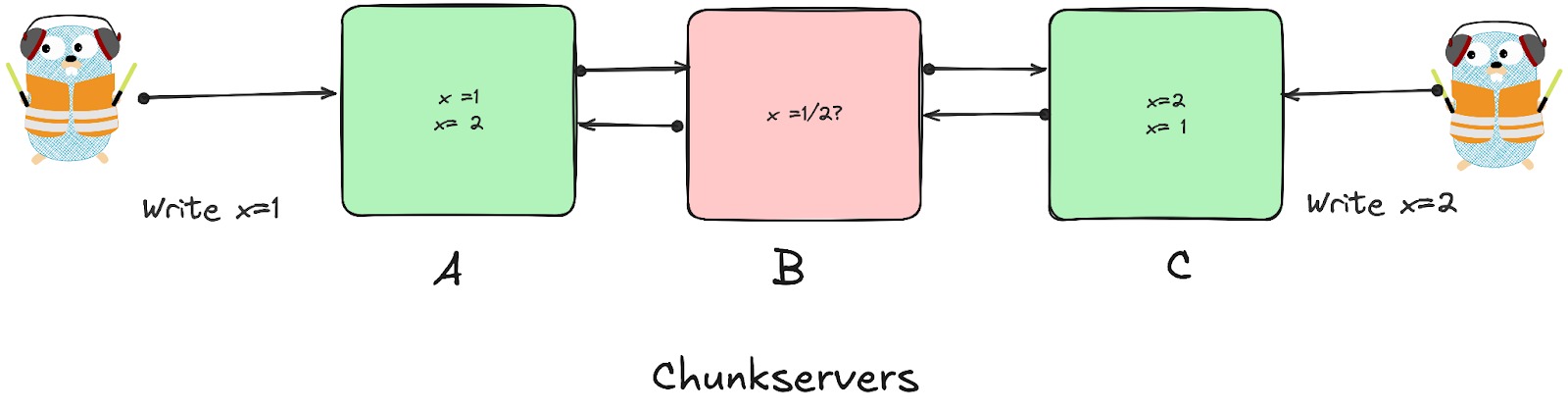

Concurrent Writes

- When we make writes to chunks, we want all replicas to see the same data!

- Only way to make this happen - write to chunk replicas in the same order on all clients.

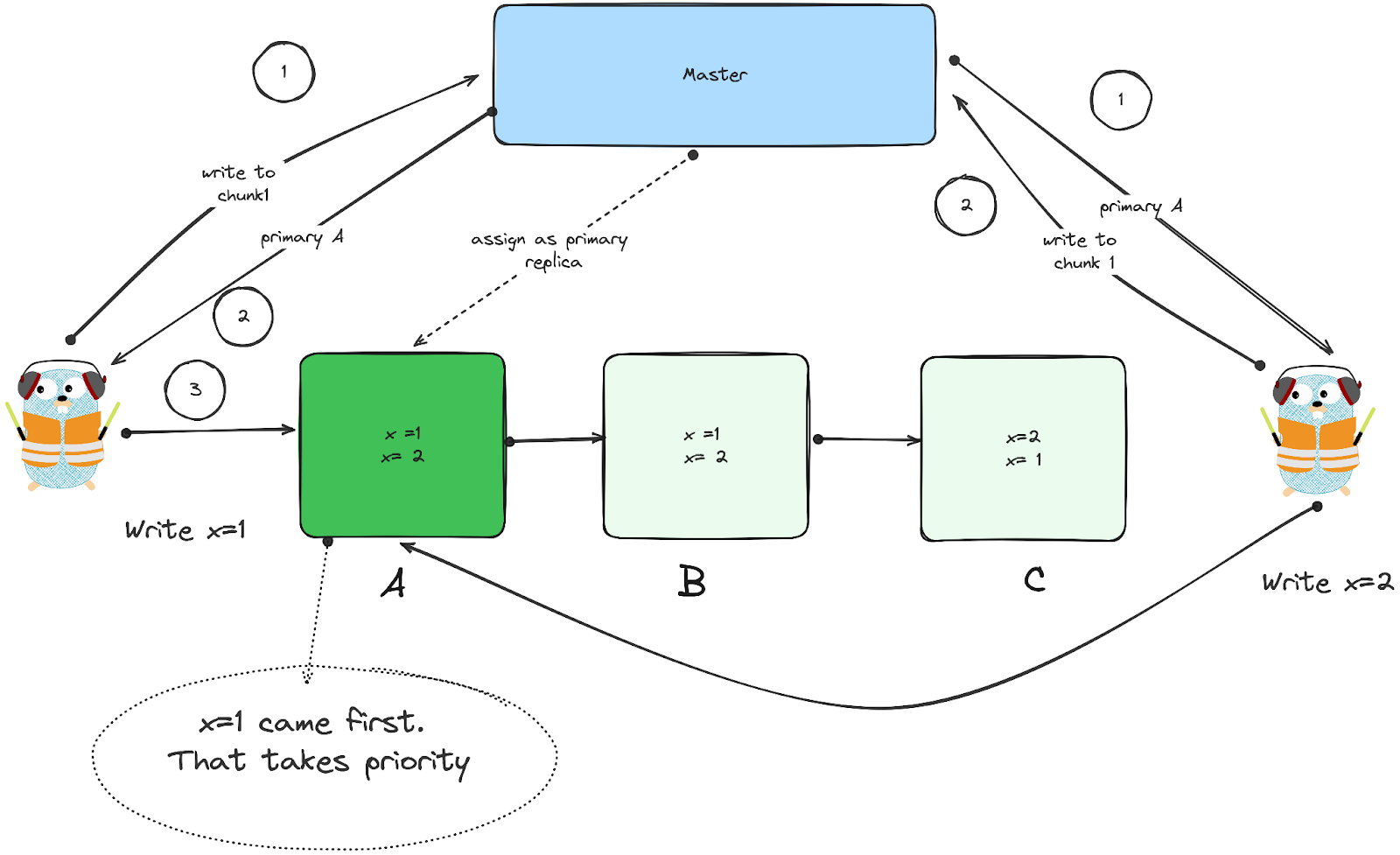

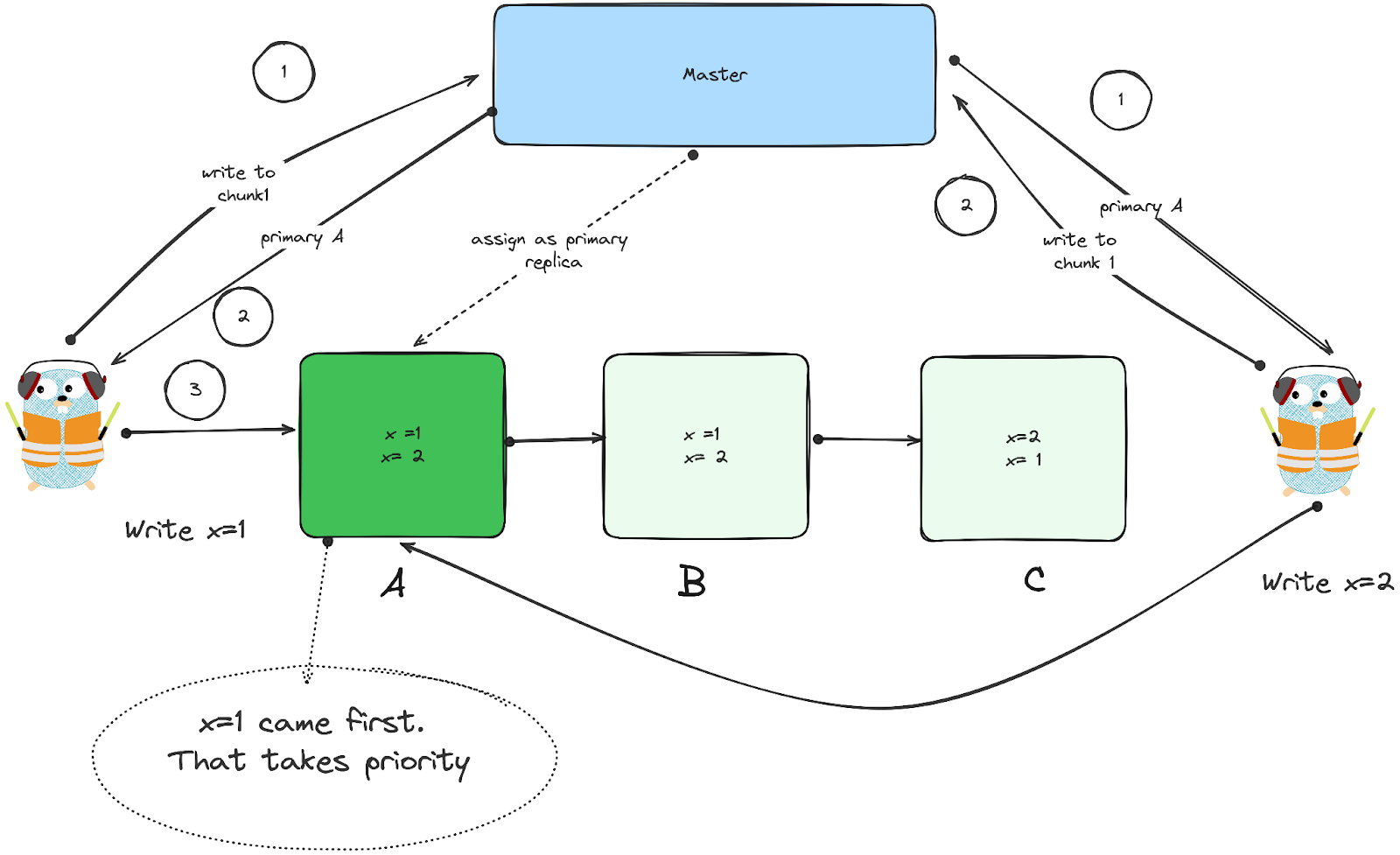

Chunk Leases

- When a client wants to write to a chunk, Master will assign one of the replicas a “chunk lease” if not already assigned.

- Chunk lease - primary node for the particular chunk, which will determine the order of writes

- Initial timeout of 60s, can be extended in heartbeats.

- Primary chunk picks the order of writes and forwards to other replicas.

Write Consistency

- By splitting the data transfer and order of writes, we get maximum throughput while keeping the data in a chunk the same across replicas.

- If we fail to apply a write to all replicas, client will retry a couple of times.

- If retries keep failing, Master checks the version number of chunks in replicas

- Each chunk has a version number, so if Master notices a replica with a lower version number than others, it will consider the replica invalid and replace it with a new node.

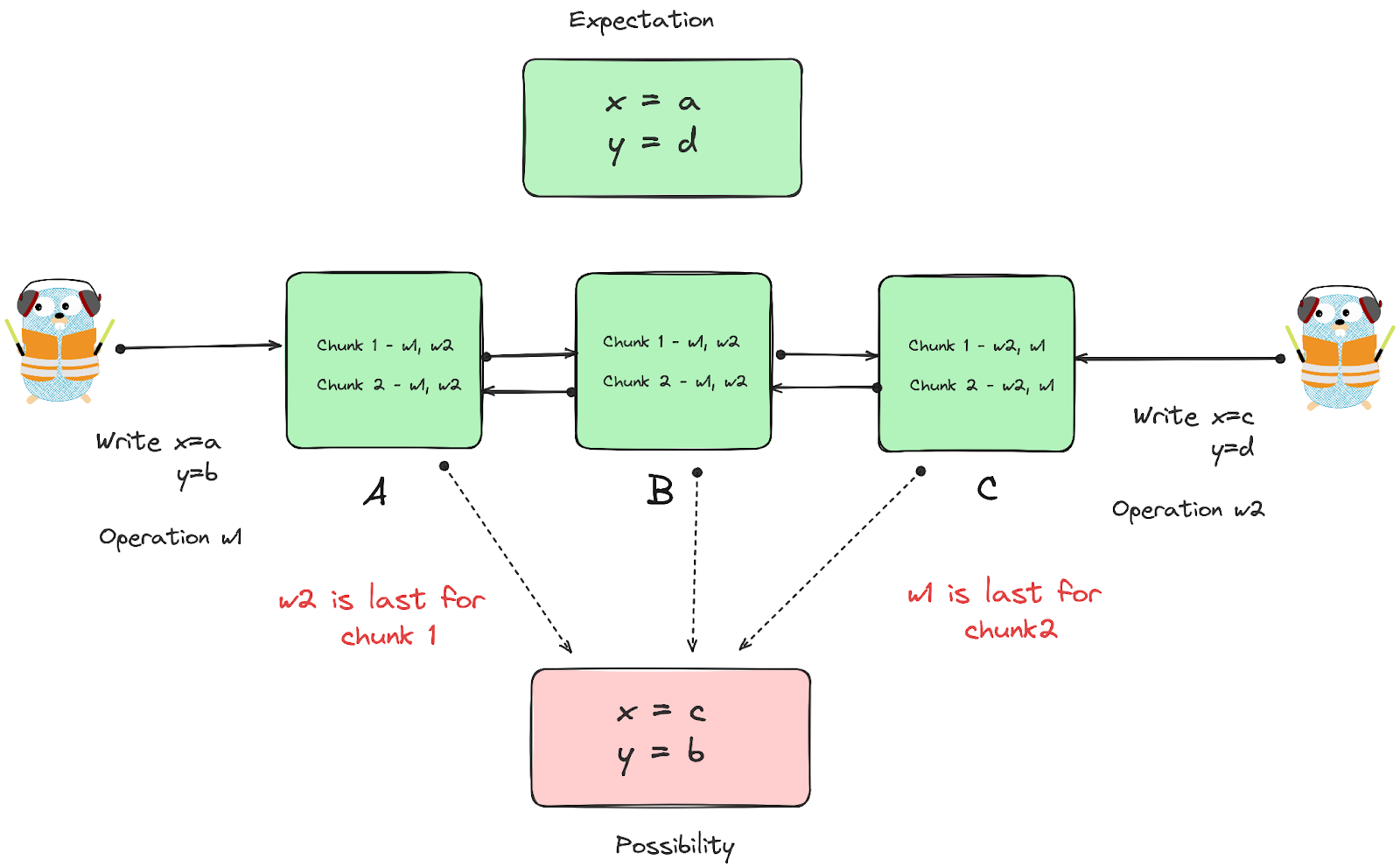

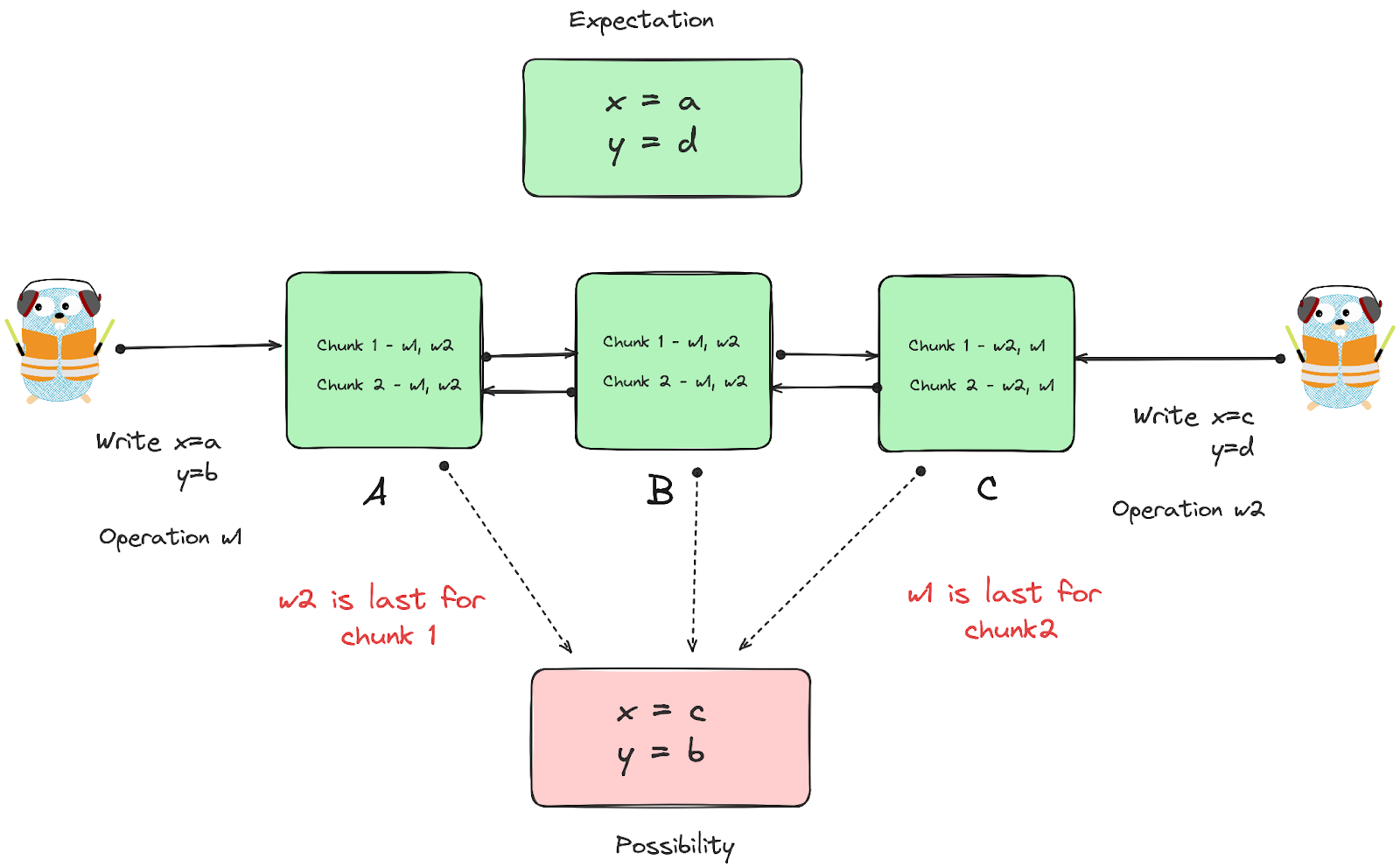

Writes to Multiple Chunks

Situation:

- If a write by the application is large or straddles a chunk boundary, GFS client code breaks it down into multiple write operations.

- x is on chunk1, y is on chunk2.

- A is primary for chunk1, C is primary for chunk2

- Writes across chunks can be interleaved.

- Need distributed locks to solve for this. Super complicated!

Atomic Record Appends

- GFS exposes an operation to append data at the end of a file without worrying about data being overwritten by any concurrent writes/needing to get a lock.

- Record append is the simplest way to ensure the data has been written consistently. When one client writes a chunk, the chunk will be locked, the other client’s writing will be arranged for the next chunk. GFS keeps every appending chunk written at least once atomically. When multiple clients write a chunk concurrently, at least once atomically keeps the record appended as multiple-producer/single-consumer.

- How does this work?

- Client pushes data to replicas of last file chunk

- If data fits in the chunk, apply like a normal write and return offset.

- Otherwise, pad the chunk to full size (Lazy space allocation), tell client to retry. Replicas are padded as well.

- If write fails and subset of replicas do not get data, client retries

- Catch

- Possibility of duplicates when write is retried.

- Downstream consumers must be equipped to handle padding/duplicates.

- Any operations should be idempotent/de-duplicated.

Implications For Clients

- Prefer appends to writes.

- No need for locking.

- No interleaving

- Readers need to be able to handle padding/duplicates.

- Use checksums to confirm the validity of the data.

- Generate idempotency keys from duplicates.

Once data is written, how do we ensure its durability?

Ensuring Durability - Replication

- GFS has

RF=3

- “Rack aware”, to place chunks across racks, to reduce the risk of rack failure.

- Data is lost when all replicas of a chunk are lost.

- Choose replicas with low disk usage and not many recently created files.

- Master “heartbeats” replicas to keep track of replicas per chunk

- Any corrupted/outdated chunk not counted – master will bring up a newer replica.

- Copies data from existing replicas

- Higher priority given to chunks with fewer remaining replicas

- Amount of replica copying at once is limited to avoid overloading GFS.

State replicas identified with version numbers. How about corrupted ones? Checksums!

Checksums

- To ensure data integrity, we basically sum up the bytes in a message

- If data doesn’t match checksum, there is likely corruption

- Checksums for every 64kb kept in memory. Meaning - 64MB/64kb = ~1000 checksums/chunk of data and kept in memory and WAL.

- For reads

- Chunkserver verifies check sums before returning data

- For append

- Compute checksums as we write.

- For writes

- Checksums are expensive.

Other Performance Optimizations

Copy On Write File Snapshotting

- Easily copy a file with another name,

- No actual copy happens. Master adds another file pointing to the same exact chunks.

- Primary replica lease revoked for chunks. Chunks must ask the Master to write again.

- When a user wants to modify one of the chunks, it gets duplicated!

- Master knows when a chunk is referenced by multiple files

- All replicas of a chunk duplicated locally (Saved network B/W)

- Master metadata updated to point to new chunk

- Can write to new chunk

Flipside - unequal # of chunks across chunkserver nodes. Solution - Rebalancing.

Rebalancing Chunks

Master checks for an uneven number of chunks across chunkserver nodes and distributes them as a background thread.

Master Namespace Concurrency

- We run the Master in a multi-threaded fashion.

- Each path has a reader/writer lock.

- This is for metadata operations (creating file path)

E.g.

/ R

/logs/server1/ R

/logs/server1/log1.txt W

/logs/server1/log2.txt

Lazy Garbage Collection

Background thread to free-up disk space containing chunks that are corrupted, stale or deleted.

Shadow Master

- HA setup for GFS.

- Warm node backing the Master. Op logs streamed to the warm node

- Can be made to take over when Master node fails.

- Stale metadata possible.

Highlights

- Failure is expected

- Op log and checkpointing in Master node.

- Version number, checksums, rack aware replicas in chunkservers.

- Design for your requirements

- Favours small appends over large writes, many reads.

- Optimized for N/W bandwidth, data transfer pipelining vs. data ordering

- Single Master is OKAY

- Allows global view of state

- Need optimizations to avoid bottlenecks

Drawbacks

Master Node Fault-Tolerance

- GFS relies on a single master node to manage metadata (file namespace, chunk locations, etc.). This can become a bottleneck, both in terms of performance and scalability. If the master node becomes overloaded, it can limit the throughput of the entire system.

- Additionally, the failure of the master node, while recoverable, can disrupt the system until it is fully restored.

Ineffective for Smaller Files / Not suited for Random Writes

GFS is optimized for large files and large sequential writes. However, it performs poorly with small files and random writes, leading to hot partitions.

Consistency Issues

- GFS only provides relaxed consistency guarantees. This means that applications must be tolerant of inconsistencies, which can occur during failures or concurrent writes.

- While this works for certain applications, such as log processing and batch jobs, it can be problematic for use cases requiring strong consistency guarantees.

High Latency For Realtime Applications

GFS was optimized for batch processing, leading to higher latency for real-time applications like Search and Gmail.

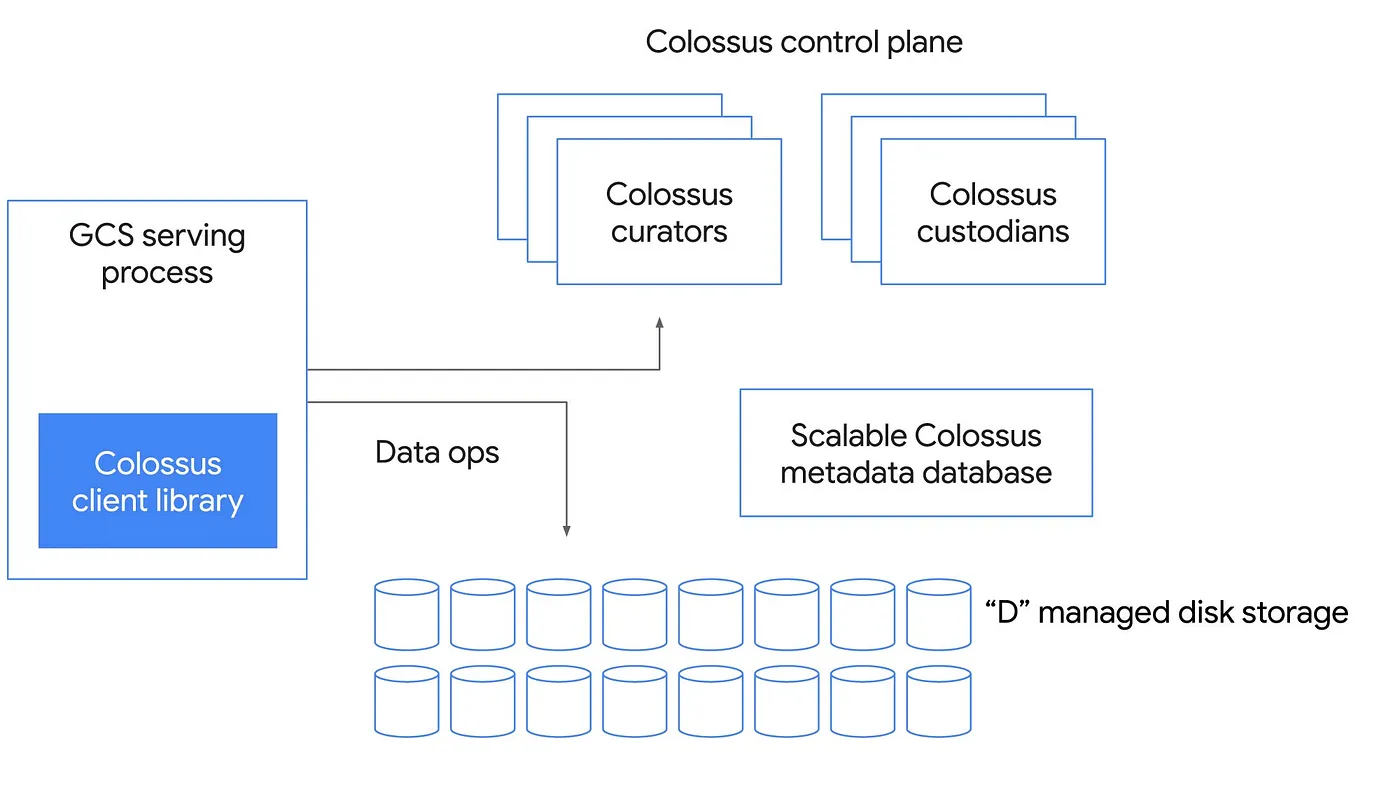

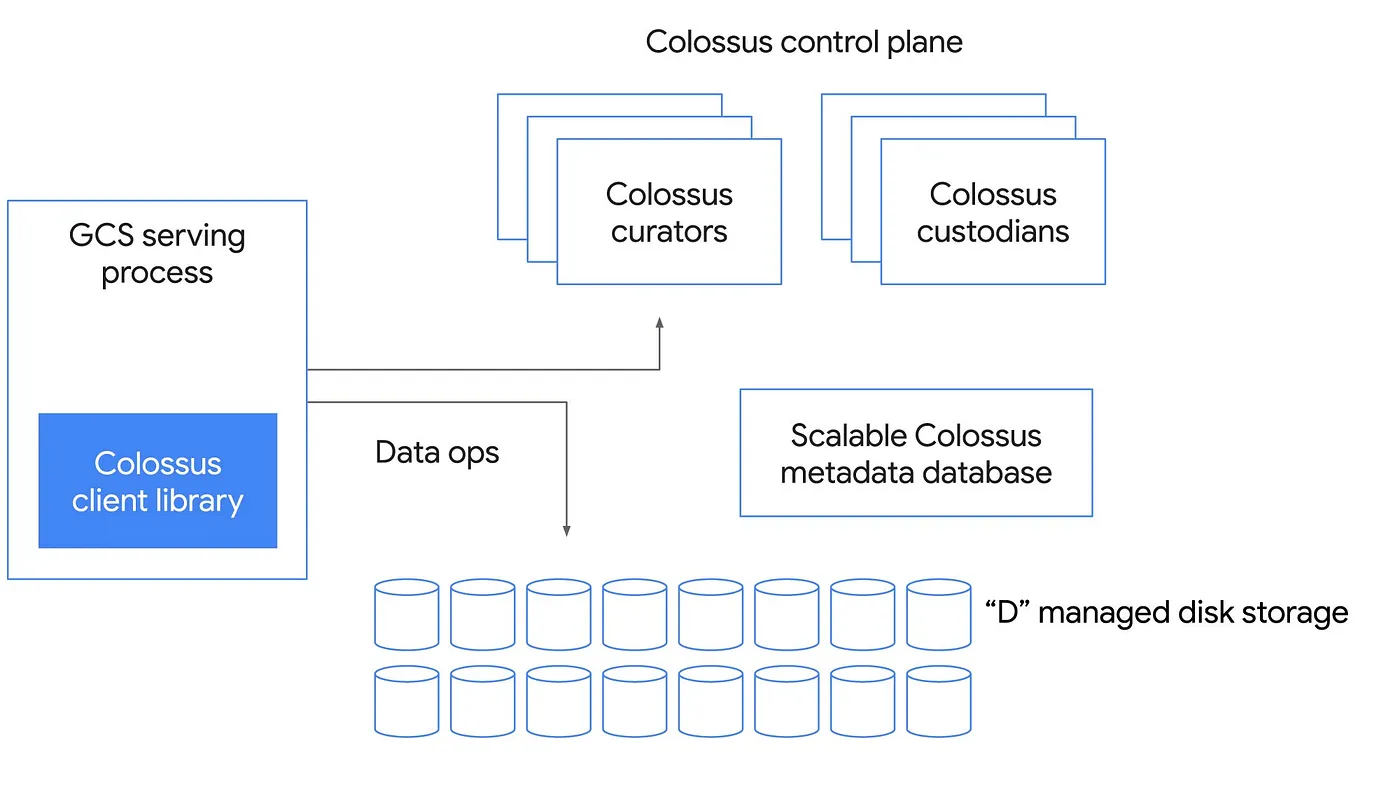

GFS vs Colossus

Differentiators

- Disaggregation of resources - Scalable Metadata System and Storage Layer.

- Also, minimal # of hops between client and disk.

Components

- Client Library

- Interface for applications to interact with Colossus.

- Control Plane

- Curators

- Scalable Metadata Service, storing it in BigTable. - 100x better than the largest GFS cluster.

- The curators manage metadata, keeps track of where all the files are located and their relevant information.

- Clients talk directly to curators for control operations, such as file creation, and can scale horizontally.

- Custodians

- Background Storage Manager.

- Manages the disk space and performs garbage collection.

- D Servers

- File servers that store data.

GFS vs HDFS

Feature

GFS

HDFS

Master Node/HA

Single master node, no HA by default

NameNode with HA and secondary NameNode

Fault Tolerance

Replication of chunks (3 copies)

Replication of blocks (3 copies, HA)

Consistency

Relaxed, allows inconsistencies

Stricter, write-once-read-many

File Access

Sequential writes, inefficient small files

Sequential writes, improved small file handling

Block Size

64 MB

128 MB

Random Writes

Inefficient

Not supported

Interface

Proprietary

POSIX compliant API

Servers

Master, Chunkserver

Name node, Data node

WAL

Oplog

Journal, edit log

Database files

Bigtable sits on top of GFS

HBase sits on top of HDFS

References

Trivia

- The original paper was published in 2003 at SOSP (Symposium on Operating Systems Principles)

- Distributed file system built for Google’s computational needs - to support hundreds of clients concurrently reading/writing to large files, while ensuring HA, performance and reliability.

Original Motivation

- Google stored dozens of copies of the entire web.

- Google was serving thousands of queries/second. Each query reads 100s of MB data and each query consumes many CPU cycles.

- Needed a large, distributed, highly fault tolerant file system.

- To build a replicated storage layer using commodity hardware – to power batch jobs. (Eventually powered other projects)

- Since GFS was primarily designed for batch workloads, it is optimized for appends rather than modifying files – users are generally expected to write large files at once than modify/write small files

Assumptions / Design Motivations

- Fault-tolerance and auto-recovery needed to be built-in.

- Standard I/O assumptions (e.g. block size) to be re-examined.

- Appends are the prevalent form of writing. And most files are written once and read many times.

- Everything must run on commodity hardware with frequent component failures.

- Aggregate read/write bandwidth more relevant instead of per client.

APIs

Not POSIX compliant.

- Read (file, startOffset, endOffset)

- Write (file, startOffset, endOffset) - Not often invoked in practice

- AtomicRecordAppend (file, data)

- Data guaranteed not to be interleaved with current atomic appends

- Returns offset where data is written

- Use-case - Pubsub on GFS or Merging data

Architecture

Overview

Consists of a Master and Chunk nodes.

- Master node maintains the metadata

- A lower layer (i.e. a set of chunkservers) stores the data in units called “chunks”.

- Each file is split into 64 MB chunks and distributed across servers.

- Why? For distributing load across multiple nodes for reads/writes.

- And most reads/writes happen in a contiguous block of data.

- 64MB is a trade-off between load balancing and providing a contiguous block of data size that clients usually operate on.

- Also, 64MB was a huge block size when GFS was originally designed.

- Chunks are stored as a plain Linux file on a chunkserver and is extended only as needed. (Lazy space allocation)

- Other points

- Less chunk metadata when chunk size is big - both for client side metadata caching and storage in GFS.

- Bad if there are many small files - since in the worst case, you can have only 1 chunk and many clients accessing the same file can create a hot partition. But not the usual case in practice.

- Clients are more likely to do a bunch of sequential operations. So, can keep persistent TCP connections.

Master

Simple design. Global state allows for better decision making.

- Stores mapping between files and chunks. (filename -> array-of-chunkhandle table and a chunkhandle -> list-of-chunkservers table)

- Has prefix compression to save file names in memory

- Chunk handles - 64 bytes.

- Chunks are replicated over 3 nodes by default. (RF=3)

Chunk Servers

Operation Log

- Master stores 3 types of information

- File/Chunk namespaces.

- Mapping between files->chunks

- Location of chunk’s replicas.

- To avoid Master becoming a bottleneck, we store the above metadata in memory. But we also persist 1.a, and 1.b in disk from time to time. 1.c. not written to reduce space.

- Operation log - (glorified) WAL

- Orders all operations

- Must be written and synchronously replicated to other nodes before Master returns any data back to clients.

Handling Master Failure

- Master can replay its operation log to restore its old state

- Note - Log only contains 1.a and 1.b. Not 1.c -> location of chunk replicas.

- Solution: Master queries chunk server to identify what they hold.

- Problem: Takes a long time.

- Other problem: Op log can be very long.

- Solution: Checkpointing state from time to time. Only read logs after the most recent checkpoint.

- Problem: Checkpointing can slow down Master.

GFS Reads

- Caching and batched reads -> fewer operations for Master.

- It is possible that one of the cached replicas has missed some writes and our client may read from it.

- Since most mutations are just appends, we don’t see incorrect data. Just less than we’d like.

GFS Writes

Considerations

- How can we write as fast as possible considering Google’s network bandwidth?

- How can we determine an ordering of concurrent writes?

Answer: By separating data transfer and ordering of writes.

Data Transfer

- Data is pipelined. As soon as A receives packets, it forwards data to B, C etc.

- Data is always sent to the closest replica that hasn’t received it.

Concurrent Writes

- When we make writes to chunks, we want all replicas to see the same data!

- Only way to make this happen - write to chunk replicas in the same order on all clients.

Chunk Leases

- When a client wants to write to a chunk, Master will assign one of the replicas a “chunk lease” if not already assigned.

- Chunk lease - primary node for the particular chunk, which will determine the order of writes

- Initial timeout of 60s, can be extended in heartbeats.

- Primary chunk picks the order of writes and forwards to other replicas.

Write Consistency

- By splitting the data transfer and order of writes, we get maximum throughput while keeping the data in a chunk the same across replicas.

- If we fail to apply a write to all replicas, client will retry a couple of times.

- If retries keep failing, Master checks the version number of chunks in replicas

- Each chunk has a version number, so if Master notices a replica with a lower version number than others, it will consider the replica invalid and replace it with a new node.

Writes to Multiple Chunks

Situation:

- If a write by the application is large or straddles a chunk boundary, GFS client code breaks it down into multiple write operations.

- x is on chunk1, y is on chunk2.

- A is primary for chunk1, C is primary for chunk2

- Writes across chunks can be interleaved.

- Need distributed locks to solve for this. Super complicated!

Atomic Record Appends

- GFS exposes an operation to append data at the end of a file without worrying about data being overwritten by any concurrent writes/needing to get a lock.

- Record append is the simplest way to ensure the data has been written consistently. When one client writes a chunk, the chunk will be locked, the other client’s writing will be arranged for the next chunk. GFS keeps every appending chunk written at least once atomically. When multiple clients write a chunk concurrently, at least once atomically keeps the record appended as multiple-producer/single-consumer.

- How does this work?

- Client pushes data to replicas of last file chunk

- If data fits in the chunk, apply like a normal write and return offset.

- Otherwise, pad the chunk to full size (Lazy space allocation), tell client to retry. Replicas are padded as well.

- If write fails and subset of replicas do not get data, client retries

- Client pushes data to replicas of last file chunk

- Catch

- Possibility of duplicates when write is retried.

- Downstream consumers must be equipped to handle padding/duplicates.

- Any operations should be idempotent/de-duplicated.

Implications For Clients

- Prefer appends to writes.

- No need for locking.

- No interleaving

- Readers need to be able to handle padding/duplicates.

- Use checksums to confirm the validity of the data.

- Generate idempotency keys from duplicates.

Once data is written, how do we ensure its durability?

Ensuring Durability - Replication

- GFS has

RF=3- “Rack aware”, to place chunks across racks, to reduce the risk of rack failure.

- Data is lost when all replicas of a chunk are lost.

- Choose replicas with low disk usage and not many recently created files.

- Master “heartbeats” replicas to keep track of replicas per chunk

- Any corrupted/outdated chunk not counted – master will bring up a newer replica.

- Copies data from existing replicas

- Higher priority given to chunks with fewer remaining replicas

- Amount of replica copying at once is limited to avoid overloading GFS.

State replicas identified with version numbers. How about corrupted ones? Checksums!

Checksums

- To ensure data integrity, we basically sum up the bytes in a message

- If data doesn’t match checksum, there is likely corruption

- Checksums for every 64kb kept in memory. Meaning - 64MB/64kb = ~1000 checksums/chunk of data and kept in memory and WAL.

- For reads

- Chunkserver verifies check sums before returning data

- For append

- Compute checksums as we write.

- For writes

- Checksums are expensive.

Other Performance Optimizations

Copy On Write File Snapshotting

- Easily copy a file with another name,

- No actual copy happens. Master adds another file pointing to the same exact chunks.

- Primary replica lease revoked for chunks. Chunks must ask the Master to write again.

- When a user wants to modify one of the chunks, it gets duplicated!

- Master knows when a chunk is referenced by multiple files

- All replicas of a chunk duplicated locally (Saved network B/W)

- Master metadata updated to point to new chunk

- Can write to new chunk

Flipside - unequal # of chunks across chunkserver nodes. Solution - Rebalancing.

Rebalancing Chunks

Master checks for an uneven number of chunks across chunkserver nodes and distributes them as a background thread.

Master Namespace Concurrency

- We run the Master in a multi-threaded fashion.

- Each path has a reader/writer lock.

- This is for metadata operations (creating file path)

E.g.

/ R

/logs/server1/ R

/logs/server1/log1.txt W

/logs/server1/log2.txt

Lazy Garbage Collection

Background thread to free-up disk space containing chunks that are corrupted, stale or deleted.

Shadow Master

- HA setup for GFS.

- Warm node backing the Master. Op logs streamed to the warm node

- Can be made to take over when Master node fails.

- Stale metadata possible.

Highlights

- Failure is expected

- Op log and checkpointing in Master node.

- Version number, checksums, rack aware replicas in chunkservers.

- Design for your requirements

- Favours small appends over large writes, many reads.

- Optimized for N/W bandwidth, data transfer pipelining vs. data ordering

- Single Master is OKAY

- Allows global view of state

- Need optimizations to avoid bottlenecks

Drawbacks

Master Node Fault-Tolerance

- GFS relies on a single master node to manage metadata (file namespace, chunk locations, etc.). This can become a bottleneck, both in terms of performance and scalability. If the master node becomes overloaded, it can limit the throughput of the entire system.

- Additionally, the failure of the master node, while recoverable, can disrupt the system until it is fully restored.

Ineffective for Smaller Files / Not suited for Random Writes

GFS is optimized for large files and large sequential writes. However, it performs poorly with small files and random writes, leading to hot partitions.

Consistency Issues

- GFS only provides relaxed consistency guarantees. This means that applications must be tolerant of inconsistencies, which can occur during failures or concurrent writes.

- While this works for certain applications, such as log processing and batch jobs, it can be problematic for use cases requiring strong consistency guarantees.

High Latency For Realtime Applications

GFS was optimized for batch processing, leading to higher latency for real-time applications like Search and Gmail.

GFS vs Colossus

Differentiators

- Disaggregation of resources - Scalable Metadata System and Storage Layer.

- Also, minimal # of hops between client and disk.

Components

- Client Library

- Interface for applications to interact with Colossus.

- Control Plane

- Curators

- Scalable Metadata Service, storing it in BigTable. - 100x better than the largest GFS cluster.

- The curators manage metadata, keeps track of where all the files are located and their relevant information.

- Clients talk directly to curators for control operations, such as file creation, and can scale horizontally.

- Custodians

- Background Storage Manager.

- Manages the disk space and performs garbage collection.

- D Servers

- File servers that store data.

- Curators

GFS vs HDFS

| Feature | GFS | HDFS |

|---|---|---|

| Master Node/HA | Single master node, no HA by default | NameNode with HA and secondary NameNode |

| Fault Tolerance | Replication of chunks (3 copies) | Replication of blocks (3 copies, HA) |

| Consistency | Relaxed, allows inconsistencies | Stricter, write-once-read-many |

| File Access | Sequential writes, inefficient small files | Sequential writes, improved small file handling |

| Block Size | 64 MB | 128 MB |

| Random Writes | Inefficient | Not supported |

| Interface | Proprietary | POSIX compliant API |

| Servers | Master, Chunkserver | Name node, Data node |

| WAL | Oplog | Journal, edit log |

| Database files | Bigtable sits on top of GFS | HBase sits on top of HDFS |